Data Availability

The first roadblock to determining the architecture for this pipeline was the available data. We need to consider 4 key modalities for this:

1. Natural Language Prompts

2. Camera Trajectories

3. RGB Video

4. 3D Scene

Based on these considerations, we found 2 main datasets:

The Exceptional Trajectories – A dataset of 115000 samples with natural language prompts and camera trajectories, along with pose data on human actors in the scene [1].

GenDoP – A better curated dataset of 27000 samples with natural language prompts, camera trajectories, and RGB video [2].

With both the datasets, there was no 3D scene data available, necessitating an approach that would separate the grounding and the text-to-trajectory aspects of the pipeline.

System Architecture

The key observation behind the architecture is that the user’s prompt can be separated into a series of anchors and trajectories. Anchors are physical keypoints that the camera should focus on, such as actors or objects of interest. Trajectories are the discrete camera movements that need to be made to go from one anchor to another.

Therefore, an LLM is used to decompose the prompt, as seen in Figure 2, and then smaller prompts for anchors and trajectories are passed into the Anchor Detector and Text-To-Trajectory Model respectively.

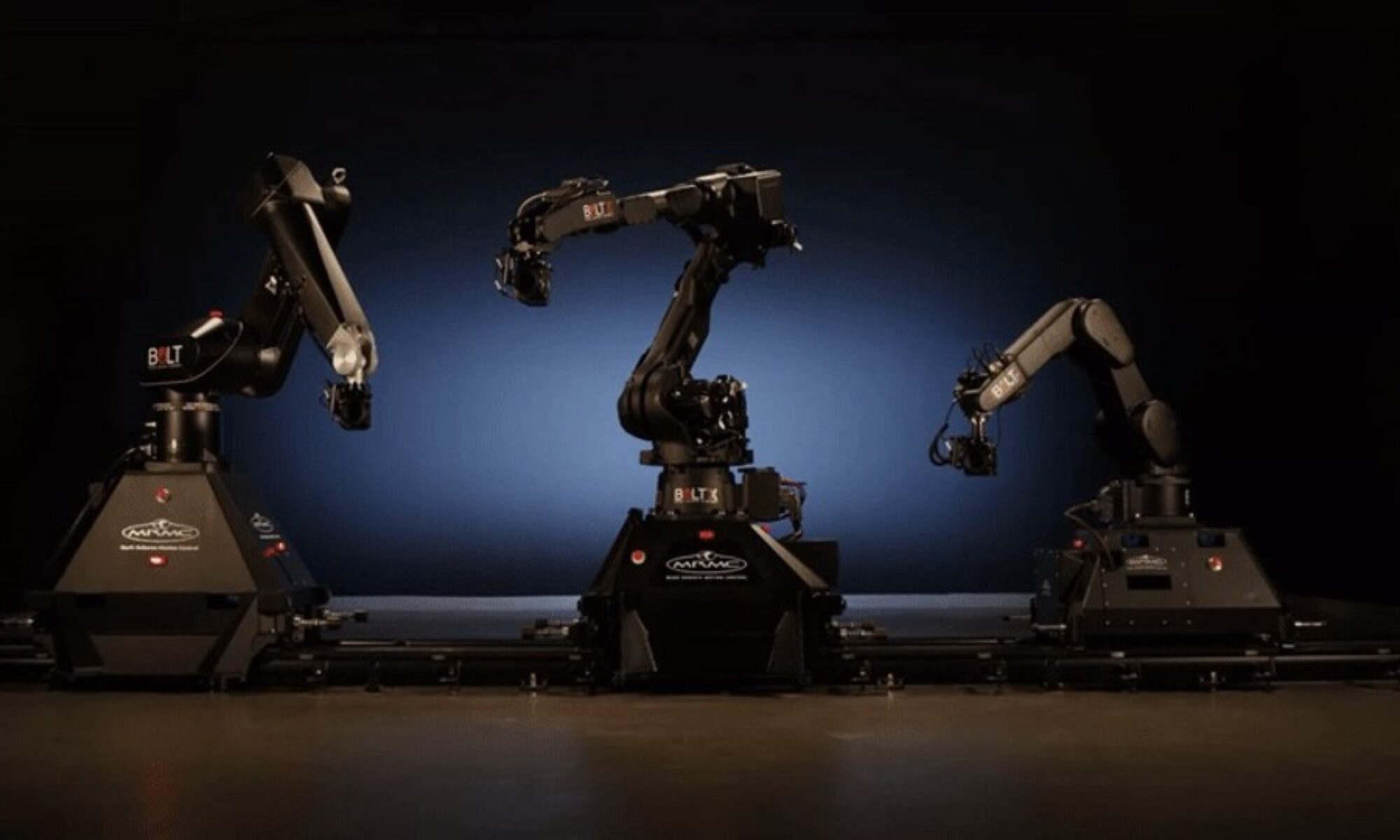

These are then combined through affine transformations to generate the final, grounded output trajectory, which is then passed into FLAIR Classic to control the robot. A small set of post-processing is done on the trajectory to ensure that the robot can physically execute the trajectory.

More details on the Anchor Detection and Text-to-Trajectory models can be seen on their respective pages.

Results

We can demonstrate this pipeline by showing results from an input prompt and scene.

Input Prompt: Slow dolly left from the actor to the laptop, then to the water bottle.

Input Scene: Figure 3 below shows the input scene, with Shaurye sitting on his chair and a laptop and water bottle on the table in front of him.

The anchors are then detected, seen through the detected objects then a screenshot of the 3D anchor points on the pointcloud below. The points are in order red-green-blue, indicating the camera should start far away then move closer to the laptop and water bottle in succession.

Fig. 5 – Anchor Points

The next step is to generate trajectories from the text prompts. Here is a visualization of one of the trajectories:

Finally, the trajectories are transformed to between the anchor points, with camera alignments adjust to view the objects properly, and some extra processing to ensure it is within the robot’s maximum reach. Below you can see it exported into FLAIR, controlling the simulated robot.

While there is still significant work to be done in further improving the smoothness and accuracy of both the detected anchors and generated trajectories, this demonstrates that the system is fully functional and can be improved iteratively over time.

References

[1] Robin Courant, Nicolas Dufour, Xi Wang, Marc Christie, and Vicky Kalogeiton. E.T. the exceptional trajectories: Text-to-camera-trajectory generation with character awareness, 2024.

[2] Mingxuan Zhang, Tianyi Wu, Jingwei Tan, Ziwei Liu, Gordon Wetzstein, and Dahua Lin. GenDoP: Auto-regressive camera trajectory generation as a director of photography, 2025. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.07083